New York Deaf Theatre

|

Press

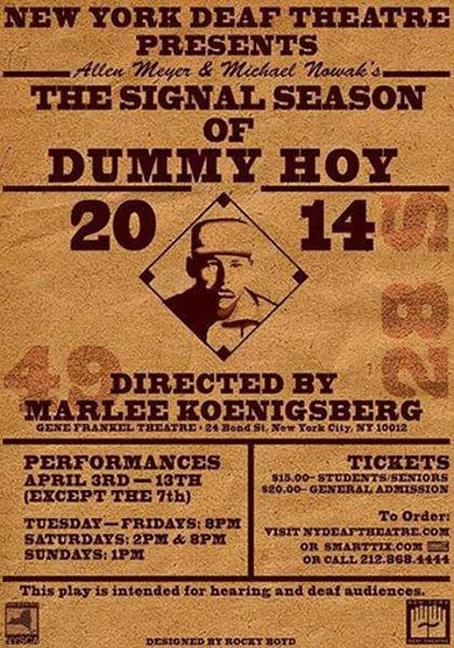

The Signal Season of Dummy Hoy

Apr 8

Posted by Rochelle Denton

Playwrights on New Plays #63 Sergei Burbank shares his thoughts on The Signal Season of Dummy Hoy

scene from production

JW Guido, Liarra Michelle | Conrado Johns

The Signal Season of Dummy Hoy charts the first professional baseball season of William “Dummy” Hoy (JW Guido) with an Oshkosh, Wisconsin team in 1886. Although deaf, Hoy’s exceptional baseball talents earn him the grudging respect of most of his teammates, as well as the team’s manager, Frank Selee (Jon Wolfe Nelson) — although the former standout player of the team, Tyler (Max Roll), holds on to a grudge for his loss of status. Through the season, as the team’s fortunes rise on the back of Hoy’s efforts, he forges new friendships: both with his roommate, Tommy (Stephen Zuccaro), and with AC (Liarra Michelle), an aspiring writer who seeks to chronicle Hoy’s journey but cannot find a local publisher willing to print a story written by a woman. The largest obstacle for Hoy, however, is his own pride and unwillingness to bend on a maddeningly simple issue: despite his batting skills, he is unable to turn around to watch the umpire’s call on a pitch before he must turn to face the next.

In an age when accommodation for those with disabilities was nigh-unthinkable (the United States was, after all, over a century from the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act), Hoy is unwilling to even ask for any special treatment: and while he can devise a system of signals with his teammates to keep up with the count, he must decide whether he is willing to ask the local umpire / league official, the Judge (Ben Prayz), to make signaling balls, strikes, safe and out calls league policy. (Aficionados of the game in the present day know that he did, and that they still are.)

Signal Season… is a bilingual production, with scenes that are spoken either in English or in American Sign Language — and many times both. But rather than being an ASL adaptation of a spoken play, the struggle of characters to speak with each other despite a communication chasm between them is an essential plot point. There are projected captions, which are leaned on by different segments of the audience at different times: for the hearing, frequent discussions and monologues in sign language require decoding, while for the deaf there are many scenes with multiple speakers and no signing at all. But rather than a concession for audience comprehension, the captions are projected in order to have the tool silenced at select moments, to throw the audience into the same incomprehension and isolation in which Hoy often found himself in the pursuit. The loss of this ability to decode the scenes (sometimes intentional, seemingly sometimes not) are powerfully felt.

JW Guido is an engaging performer; his signed monologues left this hearing and non-ASL speaking audience member torn between trying to quickly grab the subtitles in order to return to his performance. His scenes with Stacey Lightman (who portrays a wide spectrum of characters, from external figures in Hoy’s past to his internal conscience) are fluid and deeply powerful. His budding friendship with AC (the charming Liarra Michelle) is compelling and exciting, despite the struggles they have to communicate. Deserving of special praise is Jon Wolfe Nelson’s beleaguered manager, Frank Selee; it is a wonderfully precise performance that speaks with a time-capsule believability yet pulses with real empathy and humanity.

The ensemble works exceptionally well to create a believable world within the confines of the Gene Frankel Theatre, and Lauren Mills’ scenic design gels well with Mary Ellen Stebbins’ lighting design to provide the illusion of depth and expansiveness in a space that has very little of either.

This production embodies the difficulties that ensnare even those with the best of intentions to understand each other when a seemingly insurmountable communication gap exists between them; it overwhelmingly succeeds in its effort to illuminate this, and promises the rewards that make such an effort worthwhile. But as with any effort to translate between languages, there are things that get lost in the transfer; comedy is hard, and — outside of the charming, quasi-romantic missteps between Hoy and AC — there are moments where trying to make jokes that work in both languages at the same time fall a bit flat. There is a scene involving radio broadcasters trying to vamp empty airtime while grasping for details about Hoy’s playing career, and while the effort to show the importance of signing, even to hearers, is a good point, it’s tough to see how professional broadcasters wouldn’t know how to fill dead air, nor own a single pen.

A quick scan of cast biographies evinces that many of the actors — even in roles that don’t require it — are fluent in sign language; rather than a cobbling together of performers who are either deaf or hearing, either fluent in sign language or ignorant of it, this production is a gathering of many performers who are passionate about both their craft and in broadening understanding between communities. The company and its work are evidence of a larger theater community with a mission to bridge the gap between hearing and non-hearing lovers of storytelling. In the pursuit of such a goal, The Signal Season of Dummy Hoy is an admirable achievement.

Apr 8

Posted by Rochelle Denton

Playwrights on New Plays #63 Sergei Burbank shares his thoughts on The Signal Season of Dummy Hoy

scene from production

JW Guido, Liarra Michelle | Conrado Johns

The Signal Season of Dummy Hoy charts the first professional baseball season of William “Dummy” Hoy (JW Guido) with an Oshkosh, Wisconsin team in 1886. Although deaf, Hoy’s exceptional baseball talents earn him the grudging respect of most of his teammates, as well as the team’s manager, Frank Selee (Jon Wolfe Nelson) — although the former standout player of the team, Tyler (Max Roll), holds on to a grudge for his loss of status. Through the season, as the team’s fortunes rise on the back of Hoy’s efforts, he forges new friendships: both with his roommate, Tommy (Stephen Zuccaro), and with AC (Liarra Michelle), an aspiring writer who seeks to chronicle Hoy’s journey but cannot find a local publisher willing to print a story written by a woman. The largest obstacle for Hoy, however, is his own pride and unwillingness to bend on a maddeningly simple issue: despite his batting skills, he is unable to turn around to watch the umpire’s call on a pitch before he must turn to face the next.

In an age when accommodation for those with disabilities was nigh-unthinkable (the United States was, after all, over a century from the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act), Hoy is unwilling to even ask for any special treatment: and while he can devise a system of signals with his teammates to keep up with the count, he must decide whether he is willing to ask the local umpire / league official, the Judge (Ben Prayz), to make signaling balls, strikes, safe and out calls league policy. (Aficionados of the game in the present day know that he did, and that they still are.)

Signal Season… is a bilingual production, with scenes that are spoken either in English or in American Sign Language — and many times both. But rather than being an ASL adaptation of a spoken play, the struggle of characters to speak with each other despite a communication chasm between them is an essential plot point. There are projected captions, which are leaned on by different segments of the audience at different times: for the hearing, frequent discussions and monologues in sign language require decoding, while for the deaf there are many scenes with multiple speakers and no signing at all. But rather than a concession for audience comprehension, the captions are projected in order to have the tool silenced at select moments, to throw the audience into the same incomprehension and isolation in which Hoy often found himself in the pursuit. The loss of this ability to decode the scenes (sometimes intentional, seemingly sometimes not) are powerfully felt.

JW Guido is an engaging performer; his signed monologues left this hearing and non-ASL speaking audience member torn between trying to quickly grab the subtitles in order to return to his performance. His scenes with Stacey Lightman (who portrays a wide spectrum of characters, from external figures in Hoy’s past to his internal conscience) are fluid and deeply powerful. His budding friendship with AC (the charming Liarra Michelle) is compelling and exciting, despite the struggles they have to communicate. Deserving of special praise is Jon Wolfe Nelson’s beleaguered manager, Frank Selee; it is a wonderfully precise performance that speaks with a time-capsule believability yet pulses with real empathy and humanity.

The ensemble works exceptionally well to create a believable world within the confines of the Gene Frankel Theatre, and Lauren Mills’ scenic design gels well with Mary Ellen Stebbins’ lighting design to provide the illusion of depth and expansiveness in a space that has very little of either.

This production embodies the difficulties that ensnare even those with the best of intentions to understand each other when a seemingly insurmountable communication gap exists between them; it overwhelmingly succeeds in its effort to illuminate this, and promises the rewards that make such an effort worthwhile. But as with any effort to translate between languages, there are things that get lost in the transfer; comedy is hard, and — outside of the charming, quasi-romantic missteps between Hoy and AC — there are moments where trying to make jokes that work in both languages at the same time fall a bit flat. There is a scene involving radio broadcasters trying to vamp empty airtime while grasping for details about Hoy’s playing career, and while the effort to show the importance of signing, even to hearers, is a good point, it’s tough to see how professional broadcasters wouldn’t know how to fill dead air, nor own a single pen.

A quick scan of cast biographies evinces that many of the actors — even in roles that don’t require it — are fluent in sign language; rather than a cobbling together of performers who are either deaf or hearing, either fluent in sign language or ignorant of it, this production is a gathering of many performers who are passionate about both their craft and in broadening understanding between communities. The company and its work are evidence of a larger theater community with a mission to bridge the gap between hearing and non-hearing lovers of storytelling. In the pursuit of such a goal, The Signal Season of Dummy Hoy is an admirable achievement.